space is not neutral

back in undergrad, i took a course on the "politics of space", specifically in the context of japanese history. it ended up being one of the few courses that genuinely rearranged how i see the world. i want to share some tidbits from that class, and connect it to some unfolding thoughts i have around public space. so we'll meander between history & theory a bit!

we learned that only fairly recently did space itself became a topic that academics paid attention to. Foucault, writing in the 80s, described this tendency pretty sharply: space, he posited, was long considered the dead, the fixed, the undialectical, the immobile.

but in the second half of the 20th century, that started to shift. scholars began to say: "wait, space was never neutral at all!" indeed, it was shaped by power, and it shaped us back. go figure.

a key figure in that shift was Henri Lefebvre. his book the production of space introduced a now foundational idea in the humanities: space is socially produced. that is, it isn’t just a neutral platform upon which history happens, but a part of how history happens.

and if space is socially produced, that means it’s political. it means that someone decided what kind of space this would be, along with who does (and doesn't) get to be in it.

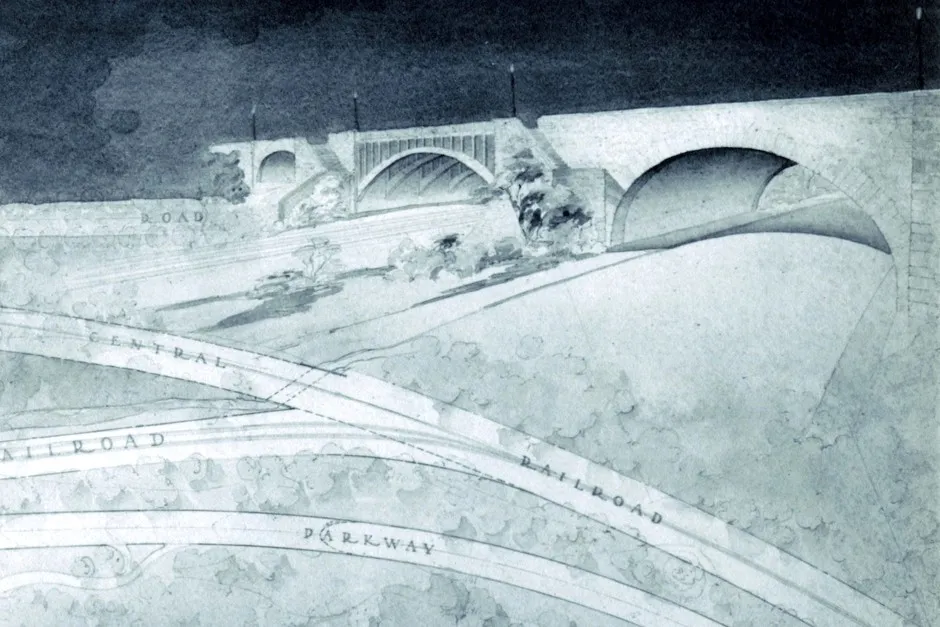

examples of this are endless. a prominent one is the story of Robert Moses, an influential NYC urban planner in the mid-20th century. when he built new parkways leading to public parks and beaches, the bridges across them were intentionally designed to be low – indeed, too low for buses to pass underneath in certain areas. this meant that anyone relying on public transport in those specified areas (ahem, low-income black and latino communities that Moses found distasteful) couldn’t take the direct route. instead, buses had to take local roads, turning what should’ve been a simple trip into a long and frustrating journey.

on paper, this might look like an engineering detail (and could easily have been shrugged off as a matter of budget limitations). but in practice, and especially considering Moses' on-the-record racist personal views, it seems quite transparent that he was baking segregation right into the transportation infrastructure.

turning to a tangentially related example in Japan: on my previous university campus in komaba (the university of tokyo), there’s a patch of overgrown land, tucked behind newer buildings, where the remnants of an old building once stood. it’s easy to walk past now without noticing. tbh, in my 4 years there, i never even stopped to read the sign that explained what the remnants were.

but that space once held a very different kind of energy. one of my juniors, James Chien-Cheng, wrote a powerful article a few years ago in our university magazine about the history of this place: the komaba-ryo (komaba dorm). it had been a vibrant self-governed student dormitory, and for decades served also as a charged site of political thought, critique, and community for the student body. throughout that historical moment, campus – and this dorm nestled right within the campus – was a place where young people were taking their education very seriously, debating the structures they were part of, pushing back against university administration, and engaging thoughtfully with the larger shifts occurring in japanese society.

but by the 1990s, the university administration had had enough. despite fierce student resistance, the university eventually shut it down. not quietly either. as James writes:

In 1996, the university cut off the power and water, hired security guards to shatter the windows, and destroyed the furniture of the remaining students. Eventually, the university sent in excavators to tear down the buildings altogether. The Gothic architecture ... vanished from the Komaba Campus along with the dormitory's culture of student autonomy.

what remained was silence. just like that, a vibrant space was intentionally erased.

again: space is not neutral. komaba-ryo was depoliticized as much it was demolished, and not to mention relegated to a long-ago history in which it can be treated as a spectacle. the void it left behind speaks volumes about what kinds of spaces are allowed to persist. as James reflects:

The underlying message is this: "student autonomy is good, but it belongs to a past that is no longer relevant, so don't try to imitate it!"

another layer to the politics of space in tokyo is movement. more precisely, what kind of movement the city encourages or discourages.

like many large cities around the world, tokyo is designed with a clear purpose: to get you somewhere. and not just any somewhere. you’re usually being funneled toward two main categories:

- where you are a productive member of society (your job)

- where you are a productive member of the economy (malls, stores, bars, restaurants, etc)

it's like the city is telling you: you cant simply exist here. you need to be moving. and if you’re not moving, you should be working. and if you’re not working, you should be buying something. oh, and don't forget to be in a hurry wherever you go!

you can feel this especially in train stations. you'll find narrow passageways, endless directional signage, and no benches. again, decisions like this seem reasonable and mundane, but often are not made by accident.

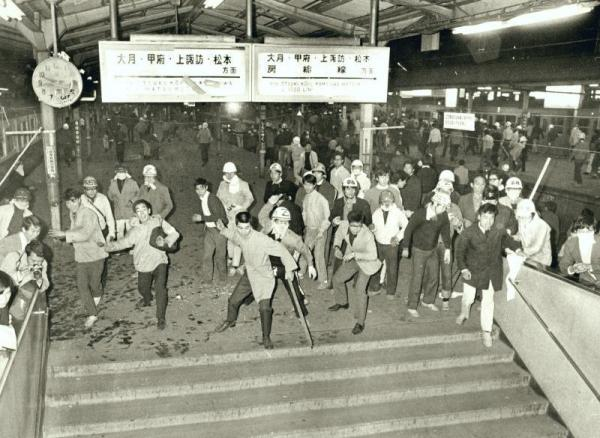

for eg., there was a huge protest in 1968 at shinjuku station - - what began as anti-war demonstrations escalated into what is now remembered as the shinjuku riot. activists were organizing “folk guerrilla concerts” right in the west exit plaza of the station, and clashes with police turned violent. then came the inevitable crackdown. riot police cleared the space, and soon after, the area was officially renamed from plaza to west exit concourse.

this was a small signage shift, but a telling one. “plaza” invites gathering and potential dissent; “concourse” demands you to keep on movin'. it marked the end of large-scale public protest in that zone, and more broadly, a warning call to the idea that city infrastructure could be co-opted for political use.

(i should note — i'm not conspiracizing that every urban design decision has some dramatic political backstory like this. but, i do think such small decisions often reflect a broader way of thinking: namely, that public space should be streamlined, goal-oriented, frictionless, etc. these days, i think the logic underpinning such decisions is more capitalistic in nature, rather than political. the corporate machine of course needs train stations to be more like a human conveyor belt than a gathering place. people got places to be and slide decks to make, yo)

on a different note, many so-called “public” spaces in tokyo feel more like you're in a freemium video game bombarded by advertisements to buy something. the design of much of the urban space in the central city reflects this, with the endless retail sprawl, billboards everywhere, vending machines filling any dead wall, convenience stores every few blocks.

this has a real effect on how people make decisions about their day. meeting up with a friend? many default to cafés. after work, many decompress at an izakaya. on weekends, many wander around busy consumer hotspots. even when you’re not trying to spend, you find yourself wound up in environments built around spending.

of course, there are still pockets in the city that resist these consumerist logics. public parks and temples are my go-tos. there are also plenty of hidden gem neighbourhoods still holding out against the slow creep of gentrification. but i would argue these places are becoming the exception.

once you start looking with these spatial-analytical goggles, you cant unsee certain things around how urban design empowers and disempowers us. you start to notice how the width of roads or height of buildings or other seemingly quotidian engineering choices affect the way you move and operate in public spaces. i invite you to go out, like my professor did to our class, to see how the space in your locality works on you. it's a great prompt for mindful walking.

the cluster of questions i keep circling back to is:

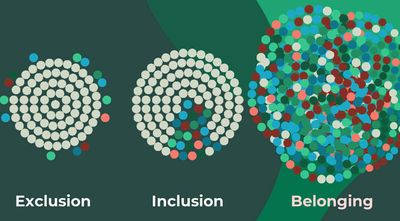

where are the spaces to just be? where in the city can you actually pause? not just between train transfers or scheduled errands, but between all the stimulus and response of our lives? where can you exist without being nudged to perform, produce, or purchase? what would it look like if, at the level of urban planning, we centered being over doing?

by “being,” i don’t just mean it in some esoteric spiritual sense, like meditating under a tree or sitting silently in a zen garden (though honestly, that sounds great and i and most others could use more time like that lol). in everyday terms, i simply mean relaxing.

yes, we have bars, izakaya, cafés, museums, galleries, shopping centers, but they all come with terms, even if implicit. they cost money, or often revolve around consumption. they can be noisy, overstimulating, not exactly welcoming if you’re not into alcohol. and most of them aren’t really built for lingering unless you're actively doing something. what we’re largely missing are spaces for relaxation not tied to capital. somewhere to go when you’re not in a rush and you don’t want to spend ¥800 on a drink just for the right to sit down.

but beyond that, i think we lack spaces that invite meaning-making, which I would argue is one by-product of spaces that invite being. i'm referring to spaces where you can decompress & deescalate & reflect on your life. and/or where you can talk about the things that actually matter to you, in a container with other people who are also hungry for that kind of depth. put another way: public spaces w/ social programming that support introspection, or dialogue, or both. from experience, i know people come alive when provided with such outlets.

in modern times, meaning-making is a mostly siloed endeavour. we do it predominantly privately: in our journals, late at night in bed when we're contemplating existence and the heat death of the universe (or is that just me?), or in the occasional heart-to-heart with a good friend. further, i would say it happens in pockets: a one-off meetup, a workshop, a class, a hobby group. i wrote more about how meaning-making is fragmented here.

there’s nothing terribly wrong with this fragmented pursuit of meaning; we're all navigating as best we can. but i keep wondering what it would mean to design for meaning-making more intentionally. to make it easier to access these deeper modes of thinking and connection, and to have this as part of the blueprint for building convivial public spaces.

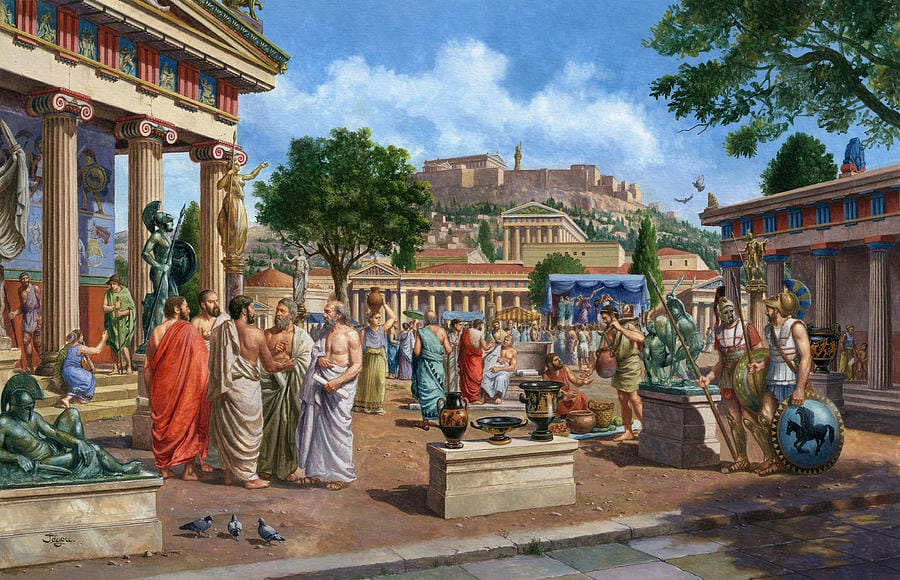

there is ample historical precedent for this around the world. the athenian stoa was a shaded walkway where people gathered to talk politics and philosophy. turkish coffeehouses were less about the drink and more about exchanging news, stories, debate. in 18th century europe, salons became informal arenas of intellectual exchange, shaping culture and politics. chinese teahouses held space for poetry, chess, gossip, performance. what's stopping us from borrowing some of these formats in our modern context?

of course, it requires more than just a few more parks or better seating. i think it’s a rather radical injunction, more than it sounds at face value, because it doesn’t just require changes at the level of infrastructure, but at the level of ideology. it would mean confronting deeply embedded systems like overwork culture (especially in japan), which leaves people too exhausted to spend time in public space even if it exists; and, related to this, the all-too-common beast of capitalism, which orients public life around consumption. the idea of designing for “being” cuts directly against these forces.

Patricia Mou has written beautifully about this in her piece on ‘publics of being’. she sketches out a vision of the city that acts as a kind of fertile ground for self-discovery and expression:

The conception of the city that I'm most excited to translate into the public sphere is the one which helps people pursue their purpose. To become more of who they are. Through that lens, the city becomes an opportunity matrix which enables citizens to come in contact with and live out their truth, transmuting that essence into art, expression, and service in accordance with their evolving capabilities. Though people are born equal, their contexts cause them to grow inequitably. Cities should be a corrective antidote by which each individual can chart their own path, as opposed to reifying, degrading, or sanctioning lines of development.

Echoed by Unger and Fainstein: “It is a place of becoming, and the fulfillment of social potential, of democratic experimentation through the efforts of citizens themselves, as free and socialized agents. We see the city, more specifically its institutions, providing the opportunity for citizens to become something else and for mutuality to be strengthened.” Implicit in this ideal is that every individual should have access to resources which enrich their capabilities to fulfill their potential. “Human capabilities constitute an important ingredient of our quality of life. The richer the capabilities, the greater the freedom to achieve and to be.” (Sen, 1999). Though there are numerous capabilities that a city can provide and equalize access to - from educational resources, healthcare access and economic prospects - I believe the capability “to be” is one that is underserved by our public realms.

on the infrastructural side, there are no easy answers either. the kind of shift towards a 'public of being' we’re talking about here would require multidimensional, cross-sectoral shifts. we’re talking collaboration across government, architecture, transportation, labor policy, economic models, education, and more. and even then, the culture has to want it. there’s no policy lever you can pull to suddenly make people feel they have time or that it’s okay to slow down.

but like all complex systems change, it doesn’t start at the level of government. it starts small, with people and local groups who are already weaving social fabric, finding ways to use existing spaces differently, or carving out new kinds of places altogether.

some things i’d personally love to see more of in tokyo along these lines:

- more events/spaces that centralize pause & play

basically, spaces designed around doing less. where you can switch off, or at least not feel pressured to perform. i’ve been following closely what reading rhythms is doing in new york - pop-up reading parties in public spaces where people gather just to read together. this is so cool. - creative reuse of old buildings

one example i love is ueno sakuragi atari – three old buildings that were almost turned into a parking lot, but were instead transformed after much resistance into a small-scale complex with artisan shops, a café-beer hall, studios, and a beloved bakery. it preserved the character of the neighbourhood and made space for intergenerational gathering and making. - public spaces that invite meaning-making

so many plazas and open zones in tokyo sit dormant most of the time, only activated for the occasional festival or seasonal market. but what if we made more intentional use of them year-round? imagine pop-up salons in these in-between spaces, or our own contemporary version of the stoa. i'm imagining low-barrier social programming that provides people of all ages and cultures and backgrounds an excuse to regularly talk, reflect, and exchange ideas in a more public forum. yeah, it's a lofty vision, but we gotta dream big, right?

if, as Lefebvre tells us, cities are socially produced spaces born out of human imagination, shaped by politics and power, then they’re up for negotiation. that’s the hopeful part for me. the good thing about knowing that space is not neutral, is that you and i have power in shaping it.